Kafka’s father, who believed in his son’s literary pursuits, often referred to his position working at the Worker’s Accident Insurance Institute as his Brotberuf—bread job.

Kafka’s father, who believed in his son’s literary pursuits, often referred to his position working at the Worker’s Accident Insurance Institute as his Brotberuf—bread job.

I’m not interested in the odd jobs that great authors held in their youth before they were writers. Every human on the planet has those histories. Kurt Vonnegut ran a Saab dealership on Cape Cod. Stephen King was a high school janitor (inspiring his first novel, Carrie). J.D. Salinger published a few short stories during the time he worked for a Swedish luxury liner (which gets closer to what interests me). Ken Kesey prepared to write One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest while being a janitor in a mental hospital. William Faulkner was once a mailman- known to take golf breaks. And Harper Lee was an airline reservationist. These are great trivia and historical amusements, rather than telling us about the way the writers lived.

I’m interested in and want to highlight here the work of authors, particularly novelists, that consumes their prominent hours, the jobs they work at, day after day, for money and bread (and sometimes passion and commitment) during the great writing, during the same days, weeks, and years that their great writing takes place.

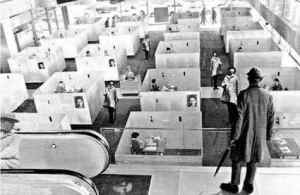

Franz Kafka has always been who comes to mind for me when I think of a writer spending their 9-5 hours at a desk in a workplace surrounded by other workers, with a secret, the fever of fiction burning in their brain. Their nights at the typewriter. Kafka worked for most his life at the Workers Accident Insurance Institute, writing claims. The most typical claims were lost limbs and fingers. Which was clearly good for his night job. He got off work at 2pm and he wrote The Trial, The Metamorphosis, Letter To His Father, The Castle, Amerika, A Hunger Artist and 8 other book-length works that were eventually published. Kafka wrote these works during the same years and decades that he enjoyed (according to some historians) and excelled at working for the insurance company. Granted he did have long periods of convalescence with tuberculosis in which to write. (I’ll settle for my weekends and Wednesdays off.) Almost all of Kafka’s work incidentally was published posthumously, against his wishes. But I don’t believe those wishes.

The other most prominent examples of working stiffs, who devoted their free time to fiction are the friends, Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Herman Melville, for nearly 30 years, worked as a customs inspector in New York City. Don’t overlook though that he spent many years at sea as well, as a merchant marine, and he was known to abandon ship to live temporarily in distant lands. Nathaniel Hawthorne was a weigher and gauger at Boston’s Custom House.

I’m partial to these jobs, since I am a Department of Health government employee, working in walking distance of New York City’s Custom’s House. And I feel I can vouch for the insurance agents, customs officials, postal workers, and the like who, despite taking pride and satisfaction in their official business, even deeply caring about the brotberuf on many days, hopelessly think of perfect sentences to come.

Most writers I know, including myself, occasionally dream about not having to work. The thought of having all day to write is seductive. In our saner moments, however, most of us realise the benefits of a day job, including security and routine. I like that Kafka treated his job with respect.I find it distasteful when artists become successful and dis the very jobs that allowed them to write or create in the first place.

LikeLike

I agree! All other work feeds the writing too- not to mention feeding the body 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s not at all surprising

that you share attributes

with many of the greatest writers & having a day job is not the defining one. The first fine author that I read & was capable of understanding & appreciate was Kafka. For the longest time I didn’t know anything about his job and unaware,or perhaps uninterested, in how he made a living. Your day job is a commendable one & goes hand in hand with your character & ideals but I am certain that it

will be your writing that will define you.

I enjoy reading everything you write & this offering is no exception. You always pull me into what I perceive as the inner Rachel. The place your thoughts are arranged & offered out in an entirely interesting and entertaining fashion.

LikeLike

Not everyone gets a Tsvi Akiva in their life. I’m glad I did something to deserve your thoughtfulness and love, Tsvi. I didn’t know Kafka was a first writer of yours. Have you heard about his views of being Jewish? It didn’t resonate much for him. XOX

LikeLike

I don’t know what to say except that this is Really Really Good writing.

Marilyn Stolzman

LikeLike

Oh, Mom. Thanks 🙂

LikeLike